The Wallace Line: Nature’s Invisible Boundary

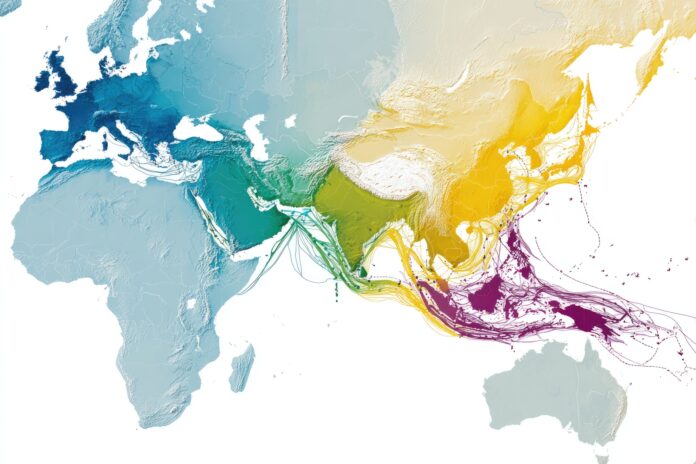

The Wallace Line stands as one of evolution’s most striking natural boundaries. This focus keyphrase highlights the incredible story of how a seemingly invisible border, just a short distance wide, has defined the animal kingdoms of Asia and Australia for millions of years. The Wallace Line’s legacy continues to intrigue scientists, zoologists, and nature lovers alike, because it shows how geography can sculpt the destinies of entire ecosystems.[3][4]

The Discovery of an Unseen Divide

In 1859, British explorer and naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace traversed the lush, tangled landscapes of the Malay Archipelago. Most importantly, he noticed that animal life shifted dramatically as he moved from one set of islands to another—despite the landmasses being just miles apart. On the Asian side, Wallace saw familiar mainland species: monkeys swung through forests, rhinos roamed, and tapirs foraged. Yet, just across narrow and deep sea straits, the mix of species resembled the marsupial-rich fauna of Australia, including cockatoos and tree kangaroos.[3][4]

What Makes the Wallace Line a Barrier?

The Wallace Line is not a wall, but a biogeographic demarcation separating the ecozones of Asia and Australasia. The reason for this division lies in Earth’s ancient history. The region it runs through, known as Wallacea, is where the deep oceanic trenches between the islands prevented most animals from crossing, even during periods of low sea levels. Therefore, while many species can swim, fly, or float over short distances, the depth and width of these straits are enough to halt large land mammals and most birds.

Because the waters are deep and sometimes wide (as narrow as 22 miles at its closest), migration was restricted for millions of years. Even birds and fish rarely cross, making the Wallace Line one of biology’s most effective invisible borders.[3][4]

Evolution on Either Side

The Wallace Line’s presence means animal evolution unfolded in virtual isolation on both sides. For example, the islands west of the line—Borneo, Sumatra, and Java—host Asian animal species such as elephants, tigers, and orangutans, while east of the line—on islands like Sulawesi and Lombok—marsupials like tree kangaroos and unique birds such as cockatoos dominate.[3][4]

This abrupt shift is not only seen in mammals, but also in birds, reptiles, and even insects. Most species have evolved to thrive only in their native ecozones, making them highly specialized and adapted to local environments. Besides that, the separation has allowed both regions to become hotspots of biodiversity and endemism, as species diversified without competition from those on the other side.

Why Don’t Animals Just Cross?

While the straits are relatively narrow, the unseen barriers are formidable. Many land animals cannot swim across deep ocean channels, and most birds prefer to keep to forests and avoid long stretches of open water because of predation risks and lack of shelter. Some flying species like bats occasionally make the journey, but this is rare.

Therefore, what appears as an easy journey for a human becomes insurmountable for most wildlife. The Wallace Line essentially acts as a filter, letting only the most mobile or adaptable species pass—yet such crossings are rare, and the evolutionary consequences have been dramatic and lasting.[3][4]

Human Boundaries Versus Animal Boundaries

Interestingly, animals aren’t just limited by natural invisible lines like the Wallace Line. Territorial boundaries are everywhere in the animal world. Many species defend invisible borders within their habitats, marked by scent, song, or physical displays. However, these lines only matter within the social context of the species. In comparison, the Wallace Line is a geological and evolutionary force, not a behavioral one.[2]

The Lasting Impact of the Wallace Line

Today, researchers see the Wallace Line as a living record of how Earth’s shifts—tectonic plate movements, sea level changes, and continental drift—can leave permanent marks on life. Most importantly, it reminds us that nature’s boundaries are often subtle yet profound, shaping life in ways that go unnoticed until someone like Wallace looks deeper. The continued study of this invisible line enriches our understanding of evolution, adaptation, and the power of natural barriers in shaping the world’s biodiversity.[3][4]

Further Reading

- Neatorama: Why Animals Don’t Cross This Invisible Line

- YouTube: No Animals Ever Pass This Invisible Border, Here’s Why

- EBSCO: Territoriality and aggression (zoology)